UX in the kitchen: An introduction to UX Spaces

User Experience is a much misunderstood discipline. For a start, in software and web development, we generally think of it as a design task, for design wonks, or some kind of process prior to real development where we determine some user needs or requirements. In particular, within web development, user experience is treated either as a step in a process, or a specialised skill, but almost never as a holistic development vision.

It is not clear to me why this is the case. Other disciplines with design aspects actually do user experience very well, but they don’t talk about it, or they do it in other ways. "User Experience" is never quoted in architecture, for example, it's just assumed that that's the point of the exercise.

UX in the Kitchen

I recently moved from a very new house to a somewhat older one. Among the many changes we had to deal with was a different kitchen. Curiously, despite the kitchen in the older house being a bit decrepit and run down, it has turned out to be easier to use than the very new kitchen in our previous residence.

This got me thinking... Kitchens are one of the most functional areas in a house, developed over hundreds (if not thousands) of years. There’s a good 30 year gap between the design of my present and former kitchen, which should be time enough to iron out any remaining kinks in the design of a functional kitchen space, yet the old one is actually better.

For a start, it is much easier to reach all the things you need. Moving between the fridge and the preparation area is pretty easy. Getting a hot pot from the stove to the sink is straightforward. But its more complicated than that… for a start, everything is within easy reach. If I forgot the oil when heating up a pan that is easy to reach. If I need plates or utensils while cooking or preparing food, I can get them without having to turn more than 90 degrees, or taking more than a step or two in any direction.

In contrast, the newer kitchen required constant twisting and bending. Cupboards were either too high or too low. The food preparation area was split between two ends of the kitchen. Moving from the stove to the sink was fairly easy, but almost every action required a full 180 degree turn. Now that may not seem all that much, but the difference when you are actually cooking is surprising. The older kitchen requires less twisting, less walking, and less foraging in deep cupboards.

The Kitchen Work Triangle

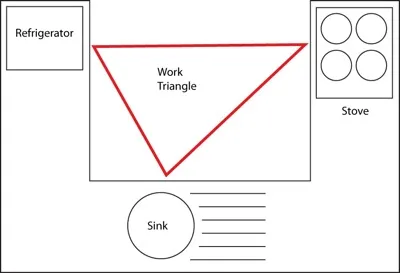

As it turns out, there’s a common model when designing a kitchen, known as the Kitchen Work Triangle. Developed by the University of Illinois School of Architecture, this model establishes a set of relationships between three key working areas, the stove, the sink, and the fridge.

There’s a few other aspects of this model...

- No leg of the triangle should be less than 1.2m or more than 2.7m

- Cabinets or other obstacles should not interfere with the legs

- There should be no traffic flow through the triangle

- There should be uninterrupted vision from each point to the others.

Because we need to cupboards to put things in, a kettle or a toaster here and there, there’s an implied design rule that these things are close to hand, somewhere along the legs. A kitchen designed along these rules can be relatively compact and quite suitable for one person to work in.

The Kitchen Work Triangle is a triumph of user experience. It prioritises the tasks users need to complete in the kitchen, such as carrying a pot of hot water from the stove to the sink, fetching eggs to make lunch, or just preparing a cup of tea.

Modern kitchens get the design treatment

On the contrary, something seems to have gone wrong with kitchen design in the early 21st century. All of a sudden, kitchen’s have dropped the work triangle in favour of several work areas, such as food preparation, cleaning, cooking, baking, and so on... Any relationship between these areas is subservient to look and feel of mass market design. The work triangle is often non-existent, but the kitchen panelling is quite nice.

Indeed, a common fashion appears to be to organise the kitchen visually into two zones, a rear galley area, and floating bar, sometimes containing the sink, at the front. This seems to work out quite well for entertaining, as you can be in the kitchen but also hang out with your guests. In itself, this is actually quite good. You can’t really entertain from the older of our two kitchens, as its partly cut off from the rest of the living area by a wall (and before a small renovation, it was in a different room altogether). So new kitchens aren’t all bad, but they seem to have lost some usability at the expense of fashion.

Arguably, modern kitchen fashion is actually a blocker to good user experience in the kitchen. Kitchen design is prioritised over kitchen usability, and because some of the fashionable design tropes actually create unusable spaces, the experience of using the kitchen suffers.

What's wrong with "User Experience"?

The Kitchen Work Triangle is a good example of how user experience can be represented and even codified, without ever mentioning User Experience. Nobody mentions user experience when talking about the Kitchen Work Triangle, because its implicit in the requirements for a kitchen that it provide a good “user experience”.

This is what we’d like to achieve with the way we design and build web applications. User Experience should be so baked into the process of design that, except when actually studying what makes good experiences, we shouldn't need to refer to it at all. Just like in the Kitchen Work Triangle, we should evaluate good design precisely because of its utility – it's "user experience" – and not as some after thought to information architecture, content modelling, or visual identity. To do that, we need to break out of information-oriented design paradigms, such as site maps, category lists, and wireframes. UX Spaces, a way of representing digital space using task mapping, rather than information structure, offers one approach.

This is an extract from UX Spaces: A New Approach To Website Design And Development, by Chris Skene, to be presented at DrupalSouth, in Wellington, New Zealand, at 4pm on Saturday February 15th, 2014.

Other sessions on UX Spaces:

- UX Spaces: A new approach to site-building and front-end design for Drupal, Portland 2013

- User-centered design for Drupal sites, Sydney 2013